Millions of people in the United States are addicted to or dependent on prescription painkillers. It is important to note that not everyone dependent on painkillers have gotten there by choice. Many of these people started off with an injury, and were given a prescription of opioids or opiates from a physician for the pain.

We are in the midst of what has been called the “Opioid Epidemic” in the United States, which is a result of a web of factors. In this article, we will explore the causes of this epidemic, and how physicians in work comp have methods in place to prevent over-prescribing these powerful drugs to injured workers.

Opioids and Opiates

Opioids and opiates both are extremely effective painkillers, prescribed by doctors to patients who are suffering from intense pain due to injury or disease. Opiates are a class of drugs that are derived from the opium poppy, while the newer opioids (such as Vicodin and Oxycontin) are a classification of drugs synthesized to imitate opiates. Both work on the opioid receptors in the brain, receptors responsible for inhibiting pain.

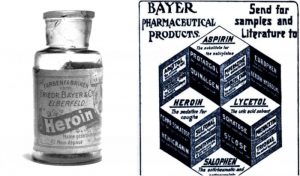

The opium poppy has been used for hundreds of years in traditional medicines, while derivative drugs like opium, heroin, and morphine, have been used for over a century. When heroin and morphine hit the American market in the late 1890’s, they were advertised to be effective against the common cold and light headaches.

Opioids were formulated as recently as the 1970’s, entering the worldwide drug market in the 80’s and 90’s. Originally opioids were marketed to doctors by pharmaceutical corporations in favor of their low cost of production, and of their low risk of dependency and addiction.

Ideally, these drugs are administered to patients in increasing strength, proportional to their pain. A patient with a fracture or chronic pain may be prescribed a low dose of hydrocodone (also known as Norco or Vicodin), while a patient with terminal cancer might be administered morphine or a higher dose of oxymorphone (branded as Opana)

As it turns out, opioids are just as addictive as opiates. They also have the potential to be much more powerful. Fentanyl, a drug created in the past 20 years, is 50 times more powerful than heroin, and has been making headlines a stunning number of overdoses around the world. A mere two milligrams of fentanyl is considered a lethal dose. First responders fear overdose from coming in close contact with someone who has themselves overdosed. The DEA has written a briefing on handling Fentanyl overdoses specifically for this exact purpose.

The Epidemic

The “Opioid Epidemic” is a term that was coined in the early 2000’s to refer to the influx of people becoming dependent and abusing opioids. Along with statistics of abuse and overdose, the onset of the epidemic was measured in the rate of prescription by doctors.

Prescription painkillers subdue the pain of an injury or disease, but also offer a powerful high, which has been romanticized in popular culture dating back to artists and musicians of the early and mid 20th century.

Because of this, drugs that are meant solely to treat intense pain develops high demand in the black market, leading to people seeking and forging prescriptions for personal abuse, and for sale to others.

The illegal sale of narcotics is not restricted to black market drug dealers. There are medical clinics that have been casually dubbed “pill mills” for over-prescribing opioids to patients to turn profit. Truly this sort of practice blurs the line of trusted physician and drug dealer, which can (and has) resulted in felony charges for physicians.

Whether intended or not, it is profitable for both pharmaceutical corporations and street-dealers to have a clientele who is dependent on their product.

Overprescription, cultural attention both positive and negative, and mass dependency, all created a perfect storm which allowed for opioids to reach an epidemic level.

What is different about workers’ compensation

In California (as in many states) there are safeguards in place which attempt to restrict the prescription of opioids to cases where they are necessary. In workers’ compensation, it is in the best interest of all stakeholders to see that an injured worker is given appropriate medication for pain management and is closely monitored throughout their recovery.

One such safeguard is the MTUS (Medical Treatment Utilization Schedule), implemented by the DWC (Department of Workers’ Compensation). The schedule guides utilization and requests, and determines the administration of treatment. Essentially, the MTUS is a list of potential treatments including medication, as well as treatments like physical therapy and yoga.

Patients are also screened for their potential for drug abuse by examining their history with substance use/abuse, family history, and psychological history. Whether an injured worker in agony with a history of drug abuse is prescribed an opioid is at the discretion of the physician.

As mentioned in a previous podcast of ours, titled “RateFast Podcast: Came for Surgery, Left with Antidepressants?”, a patient who comes into a clinic for pain can sometimes discover a problem with a psychological component and may be treated for depression or anxiety, systematically treating an underlying cause of the pain.

CURES (Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System), is an online tool that physicians, law enforcement officers, and a few other parties can use to check and see where a patient receives medication, and if they are already receiving medication from another clinic. Interestingly CURES registers when drugs have been prescribed to people’s pets as well. Doctors have had calls for verification because their dog had also recently received painkillers.

It is important for all medical professionals to have a treatment plan which includes weaning the patient off of opioids.

Conclusion

In recent years, the prescription of opioids in the United States has decreased. This is especially true in workers’ compensation. Meanwhile, education about narcotics and efforts to treat those who are dependent upon them has increased.

There is no doubt that the use of potentially harmful prescription painkillers is an effective pain management tool in many cases, though the awareness of the potential damage it can do to a person (and those around them) has caused greater scrutiny and increased interest in alternative methods of treatment.

Until a drug that is equally effective without potential for abuse hits the market, physicians will continue to prescribe opioids to patients. It is the responsibility of physician’s to make sure that their authority to prescribe opioids are doing more help than harm.